Not every attempt at portraying autism hits the mark. Here’s a look at the movies and TV shows that seriously fumbled representation – and what they got so, so wrong.

Hollywood doesn’t always get it right – especially when it comes to portraying autism. For every nuanced, heartfelt depiction, there’s a tone-deaf performance or a script that confuses stereotypes for substance. Over the years, plenty of films and shows have tried to “capture” the autistic experience, but ended up missing the mark entirely, often turning complex realities into caricatures.

This list dives into some of the most misguided portrayals of autism in pop culture – productions that, whether through ignorance or outdated tropes, did more harm than good. From big-budget misfires to TV’s well-intentioned blunders, these examples remind us that representation matters – and that empathy should never be lost in translation.

Music (2021)

The decision to cast Maddie Ziegler, a non-autistic actor, as Music, a nonverbal autistic teenager, instantly raised eyebrows – and it’s one of the film’s biggest missteps. The movie leans heavily on melodrama and musical interludes, sometimes at the cost of depth: restraint scenes and “meltdown moments” often feel choreographed for spectacle rather than realism. Autistic viewers and advocates criticized the dangerous idea that non-autistic guardians or creatives can fully “interpret” nonverbal autism without authentic lived experience. Worse, the film seems to use disability as a plot device: Music becomes the vehicle for emotional arc of others more than a complex individual in her own right. The lack of supportive social or institutional context (school, therapies, everyday supports) makes the depiction feel isolated and unrealistic. It’s a case of good intentions colliding with problematic tropes – of non-autistic people deciding what autism “looks like.”

The Fanatic (2019)

Plot twist: The Fanatic doesn’t simply botch characterization; it weaponizes it. John Travolta plays Moose, said to be on the spectrum, but the film repeatedly uses that as a shorthand for creepy, obsessive, and dangerously impulsive behavior. The writing never bothers to nuance Moose’s autism – it's opaque whether the condition is high-functioning or severe, making the portrayal feel exploitative. His behavior becomes less “person” and more “freak show” whenever it serves the plot’s thriller aspects. Add to that the filmmakers’ choice to use what seems like awkward, exaggerated mannerisms for laughs, or horror, rather than empathy. Viewers and critics have noted the film seems to hate – or at least mock – its protagonist’s struggles, rather than understand them. Essentially, autism becomes a punchline or excuse rather than a lived experience.

The Predator (2018)

In an attempt to add “depth,” The Predator introduces a character, Rory McKenna, with autism – but the execution turns into a cringe carnival of tropes. Autism is waved around as some kind of superpower or evolutionary leap (spoiler: it isn’t), especially when other characters talk about it being the “next step in human evolution.” That kind of messaging doesn’t empower; it reduces. Rory is portrayed as uniquely gifted because of his autism, which feeds into the old “autism = genius, super-ability” stereotype more than anything realistic. The movie also uses his differences to fuel plot convenience – needing his genius to unlock things while ignoring what autism often really involves: struggle, support needs, sensory issues. Even among action and spectacle, Rory’s autism is coded but inconsistent, never grounded in real lived experience.

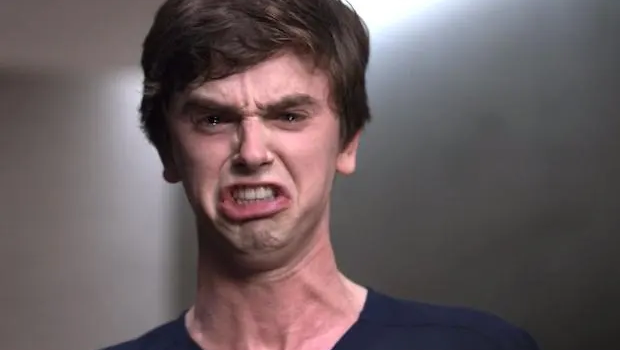

The Good Doctor (2017–present)

This show sells itself as groundbreaking, but much of the autism community sees it as a mish-mash of stereotypes. Shaun Murphy’s “savant syndrome + social awkward genius” combo is one that many say reinforces the idea that autistic people are only valuable if they are exceptional. Add in situations where his odd behavior is always either a plot hurdle or a dramatic twist: it’s emotionally manipulative in ways that play to misconception. Also, key creatives (writers, consultants in early seasons) are non-autistic, which risks the portrayal being shaped by outsider assumptions rather than lived truth. Some episodes depict Shaun misunderstanding patients, acting insensitive, or being forgiven in unrealistic ways simply because “well, he's autistic.” That kind of framing normalizes excuses for behavior without showing accountability or growth. The show builds a character people love – but often for the wrong reasons.

Atypical (2017–2021)

There’s charm in Atypical, and moments where it seems to want to do right by its autistic protagonist, Sam. But it too stumbles into shallow waters. Sam is played by a non-autistic actor, and many have pointed out that his character often feels like autism as seen through neurotypical lenses – traits exaggerated for comedic or sentimental effect, with little of the internal struggle or diversity that actually exists in the autistic community. Sense of high functioning, mild social awkwardness, but rarely the messiness: comorbidities, sensory overload, meltdowns not followed by neat resolutions. Also, the show sometimes treats autism as the defining aspect of Sam’s identity – he often is his autism, rather than being more than it. For all its good intentions, it often reinforces the idea that one kind of autism is the “acceptable” kind.

The Night Clerk (2020)

This one tries to mix psychological thriller with autism “depth,” but ends up feeling exploitative. Bart, the protagonist, has Asperger’s-syndrome (on the autism spectrum), and the film leans hard into his difficulties with social cues – yet the performance often tips into caricature. Hidden cameras, voyeurism, awkwardness, and constant reminders that he’s different become plot devices rather than opportunities for compassion or insight. The movie seems more interested in bending the condition to justify creepy thriller tropes. Dialogue and character interactions often feel forced: his differences are used to explain behavior that would feel unbelievable if he weren’t autistic. And despite some sympathetic moments, there’s little care in building him as a fully realized person with hobbies, nuance, or normal-life details beyond “he’s weird, he can’t read people.” The viewer is meant to pity, fear, or root for him, but rarely to truly understand.

The Big Bang Theory (2007–2019)

Sheldon Cooper wasn’t officially labeled autistic – creators repeatedly denied he had a diagnosis. But as seasons pass, he’s drenched in autistic coding: rigid routines, resistance to change, hyper-focus on science, troubles with sarcasm and social cues. The problem starts when those traits are used almost exclusively for laughs, as quirks, rather than respectfully exploring what having those traits feels like in the real world. There’s charm in Sheldon’s eccentricity, but the show rarely gives him authentic moments of struggle that aren’t resolved by comedic cliché. Also, his depiction leans heavily into “genius scientist,” reinforcing stereotypes that autistic people are only interesting when they’re extraordinarily gifted. It sells a one-dimensional idea: be weird, be awkward, but be insanely smart. That undercuts real autistic experiences, which are varied, messy, and often invisible to TV’s narratives.

Molly (1999)

Molly gives us a story about a 28-year-old autistic woman who’s been institutionalized since childhood, then goes through an “experimental” treatment that temporarily makes her more “normal” – a cliché so old it has cracks. The film treats her autism as inconvenience for everyone else first: her brother, her caretakers, she herself becomes a tool to teach Buck humility, responsibility, and compassion. There’s very little realistic portrayal of daily life, sensory overload, or the fact that many autistic people don’t want or need to be “cured.” It’s full of melodrama, with scenes designed to elicit tears more than to foster understanding. Even the “cure” concept is problematic: implying that normalcy is better, that autism is a deficit to be fixed rather than a way of being that needs accommodation. The film ends with Buck telling Molly’s autism is something to accept – but only after it’s been “improved” and “lost” and “regressed” and all that. It’s sentimental, yes, but deeply misguided.