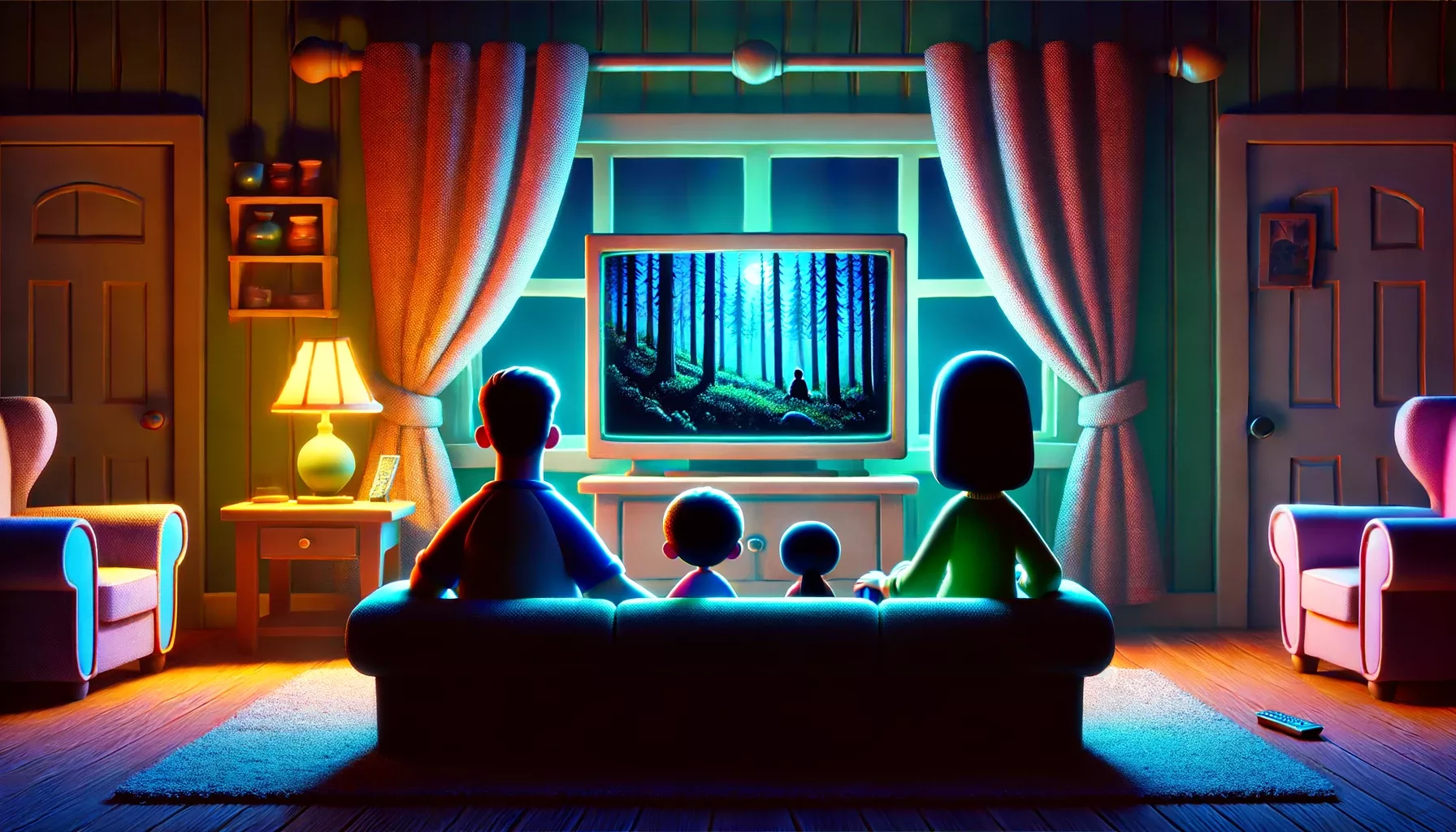

Featuring neither Link nor Zelda, but a lot of heart.

As the first fully-fledged The Legend of Zelda game on a handheld platform, Link's Awakening (1993) effectively faced an uphill battle, having to match the quality of its predecessor A Link to the Past (1991) on the technologically vastly inferior Game Boy system.

Luckily, it did not have to face this battle alone, thanks to a completely different team at Nintendo developing and releasing another – nowadays largely forgotten – Game Boy game the year before, which Link's Awakening was able to draw from for its engine and design.

No Rude Awakening

The first The Legend of Zelda (1986), known for popularizing the action-adventure genre, was famously a result of Nintendo game designers Takashi Tezuka's and Shigeru Miyamoto's vision to give players a digital world to freely and explore and uncover the mysteries of, resembling the latter's own experience of wandering around Kyoto as a child.

Later entries like A Link to the Past would streamline the gameplay, making progression more story-driven. Shortly after its release and after programmer Kazuaki Morita had started making Zelda prototypes for Game Boy, Tezuka intended to port A Link to the Past over to the new platform. Soon however, the project turned into its own game.

The final result, Link's Awakening, stood out for telling its own story unrelated to the greater Zelda narrative, having Link shipwreck on an unusual island, which turns out to be inside of a dream of a deity called the Wind Fish, which Link needs to escape by collecting melodies from across the island. The game became a huge critical and commercial success, with praise directed towards its premise and technical achievements. It would receive a remaster in 1998 and a remake in 2019.

Vast Yet Tiny Adventures

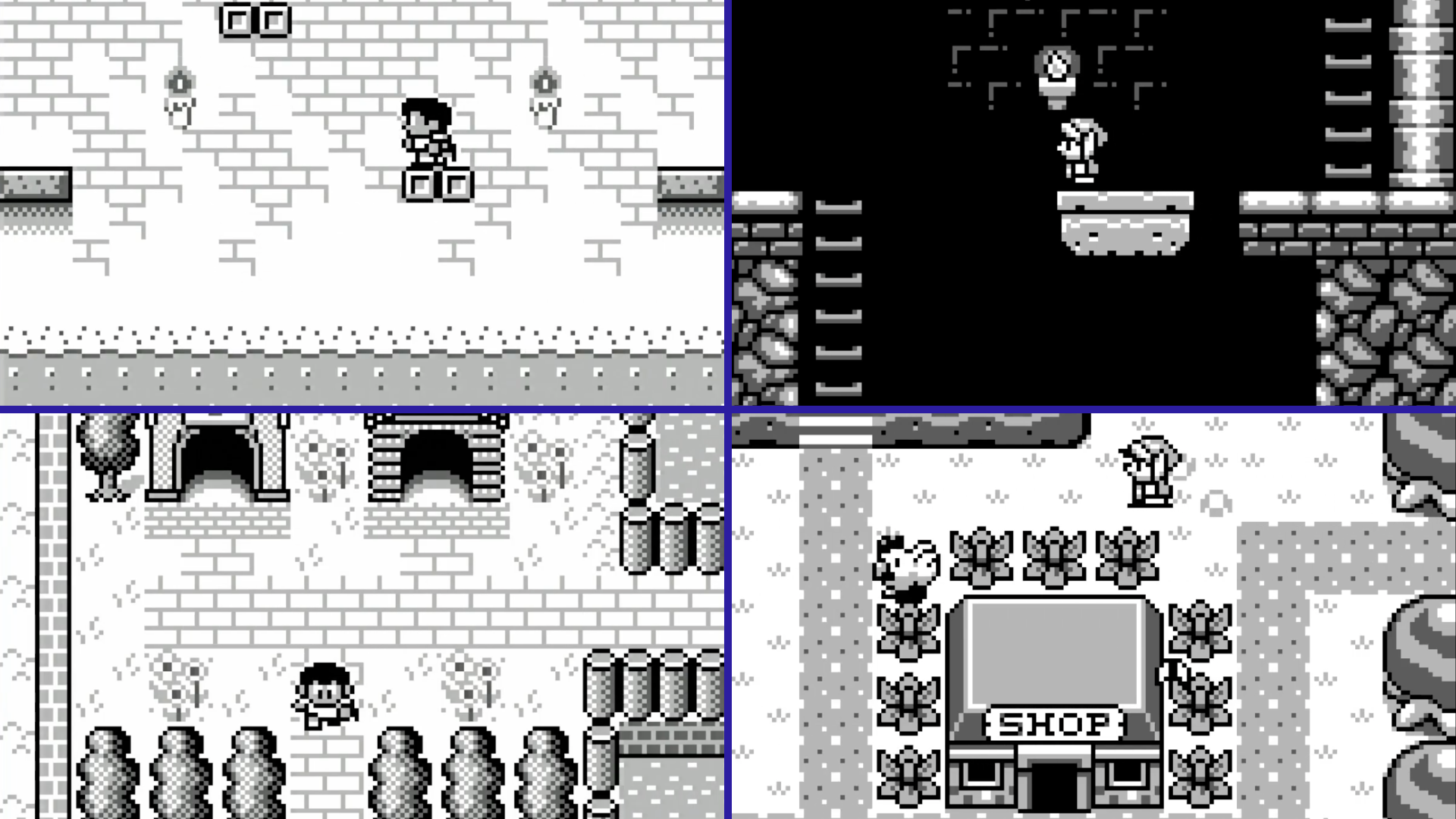

Making a game of this scale for the Game Boy was very challenging, seeing as the team only had 1 MB of ROM space on the cartridge and merely 8 KB of WRAM and 8 KB of VRAM on the system to work with. So how did they manage to create the engine for an action-adventure game that circumvented these restrictions in just one-and-a-half years of proper development time?

Turns out, they didn't. Shortly before, a different team at Nintendo had made their own action-adventure for the handheld with The Frog For Whom The Bell Tolls (1992), also known by its Japanese name Kaeru no Tame ni Kane wa Naru. That team had to invent a kanji-to-8×8 tile conversion system, build a more complex text pipeline, and come up with an engine that was adapt to the scarce memory of the hardware.

On the audio side, Kazumi Totaka, who later composed the memorable and story-relevant soundtrack of Link's Awakening, was finding new ways to compress expressive music into just a few channels while balancing space for sound effects. In many ways, this Japan-exclusive title paved the way for Zelda's Game Boy success story.

Strategic Creative Decisions

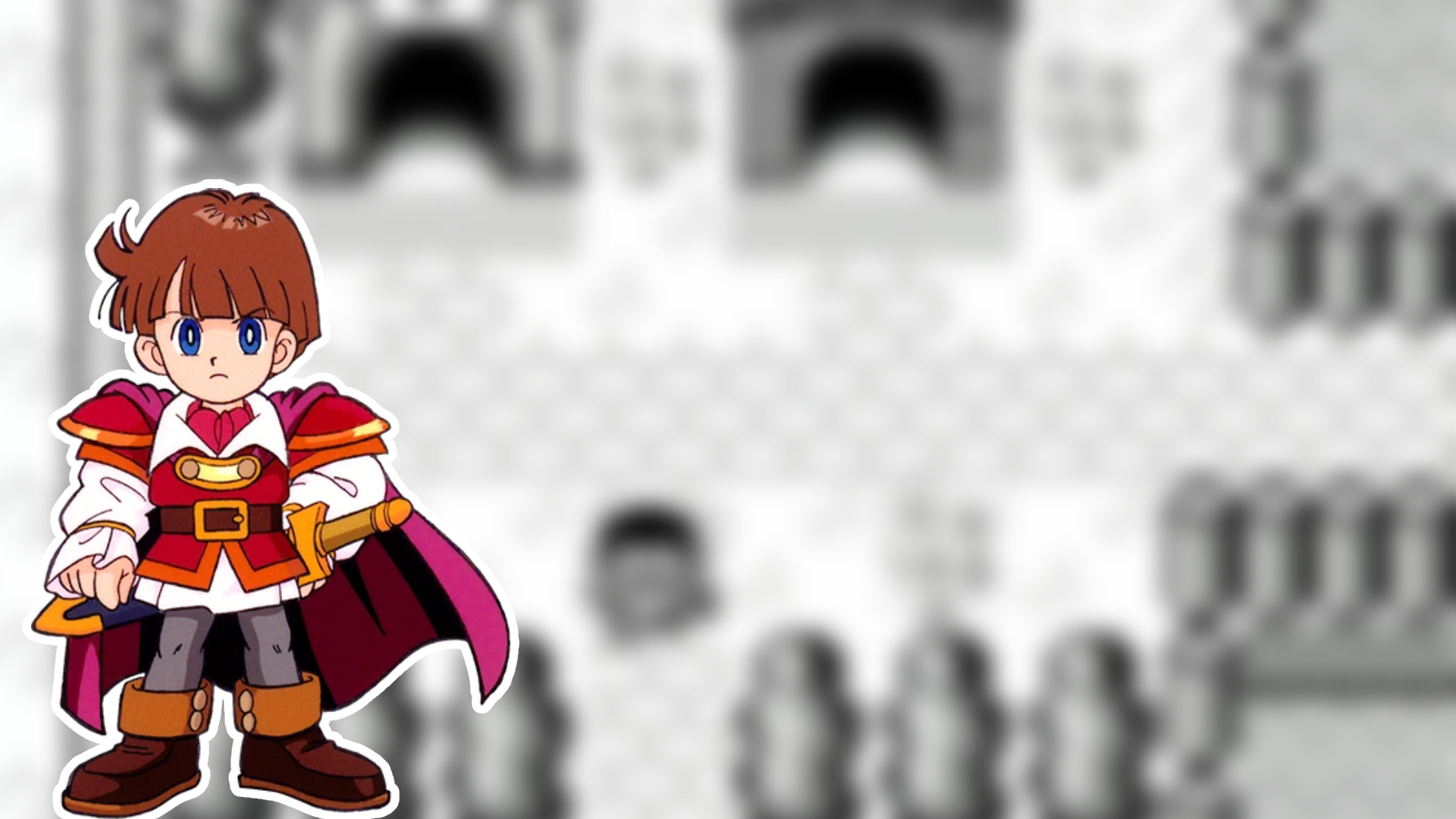

Reflecting Nintendo's strategy to develop novel handheld experiences and writer Sakamoto's ambition to subvert fantasy RPG tropes, The Frog for Whom the Bell Tolls sees players controlling the Prince of Sablé (that owns an Assist Trophy from Smash Bros.) on his quest to rescue Princess Tiramisu while racing against his rival Prince Richard. Throughout the Kingdom of Mille-Feuille, the prince uncovers secrets and transforms into a frog or snake to solve puzzles.

Gameplay alternates between top-down exploration of towns and overworld areas and side-view platforming sections, a feature which would return in Link's Awakening. The game makes use of an unique automatic battle system: Bumping into an enemy triggers a stats-based scuffle, with health ticking down in real time until one side collapses. Progress is achieved by collecting items and talking to quirky NPCs.

These mechanics reflect the Game Boy's limits: Automatic battles reduced the per-frame CPU work, the dual perspectives made use of the tiny RAM and VRAM budgets and game's Japan-exclusivity can partly be blamed on its proprietary kanji-dialogue-pipeline. The end result was a uniquely streamlined, yet ambitious adventure tightly bound to its hardware.

A Hero's Rest

Aside from noting the technical achievement The Frog for Whom the Bell Tolls marked for the Game Boy, contemporary critics lauded the game for its humor and unique ideas. While reviewers nowadays sometimes consider the title a bit shallow and too easy, it can't be denied that it was genuinely popular in Japan.

Some of its main characters would even go on to appear in Link's Awakening (Prince Richard) and the Smash Bros. series (Prince of Sablé). Unlike Link's Awakening though, the title never received a remake, being often overshadowed by its spiritual successor. Even its re-releases on the Nintendo 3DS in 2012 and Nintendo Switch in 2024 remained exclusive to Japan.

The Frog for Whom the Bell Tolls has, however, garnered somewhat of a cult following in the West, thanks in large part to the translation patch a modding team surrounding user "ryanbgstl" published in July 2011. In somewhat of a full-circle moment, they managed to circumvent the original's kanji pipeline by adopting the same in-game text system present in the English translation of Link's Awakening.