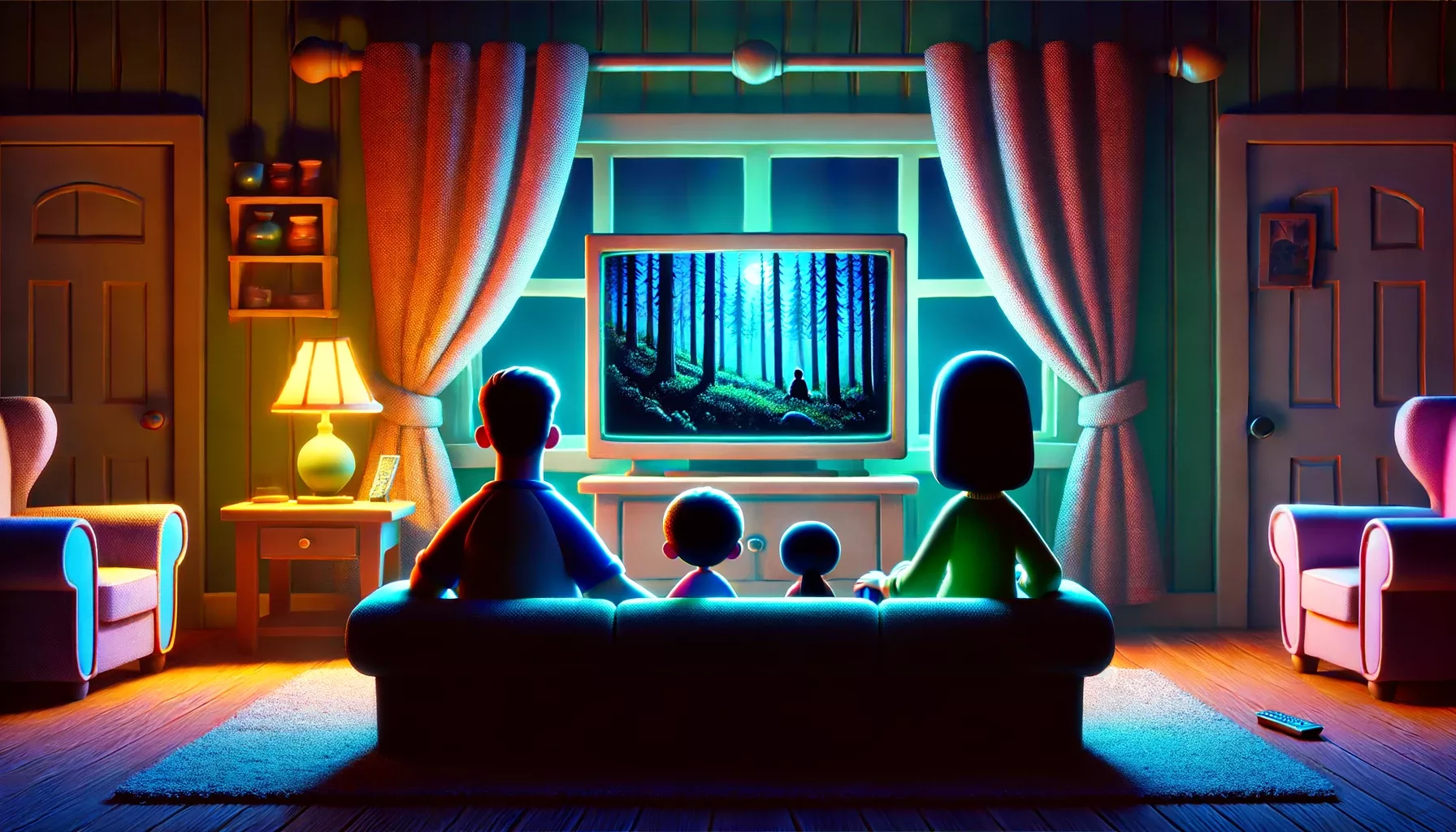

In a scene-by-scene breakdown for Vanity Fair, paleontologist Dr. Mark Loewen examines how scientifically accurate the dinosaurs of Jurassic Park really are.

Ever since Jurassic Park first came onto movie screens in 1993, audiences have been both dazzled and terrified by its lifelike dinosaurs. But how well does Hollywood hold up to actual science? To separate fact from fiction, Vanity Fair brought in Dr. Mark Loewen – a paleontologist at the University of Utah and the Natural History Museum of Utah – for a scene-by-scene breakdown of dinosaur accuracy in the franchise. In the video "Paleontologist Reviews Jurassic Park Scenes," Loewen puts Spielberg’s creations under the microscope and reveals just how much (or how little) these cinematic creatures have in common with their real-life counterparts.

How Realistic Are The Dinosaurs In Jurassic Park?

Spoiler alert: there’s a lot of dramatic license. But there’s also surprising accuracy, and some moments that even impressed a seasoned expert. Let’s dig in.

T-Rex: The Sound of Fear (Mostly) Checks Out

Did dinosaurs make noise? Absolutely. Was it this exact heart-stopping roar? Well, maybe not – but Loewen says T-Rex’s massive resonating chambers could’ve produced a sound that would "stop your heart for a second." So yes, some creative liberty, but still grounded in plausible biology. Vision, however, is where the franchise blinks. Contrary to the film’s famous “Don’t move, it can’t see us” logic, T-Rex likely had better vision than a hawk. Loewen confirms: binocular sight, overlapping field of view –this predator saw what it was eating.

Dilophosaurus: A Total Work Of Fiction

The venom-spitting, frill-popping Dilophosaurus that took out poor Nedry? “The worst dinosaur in the franchise,” says Loewen. In reality, this dino was much bigger (25–30 feet) and completely devoid of frills, venom, or spitting abilities. There’s no evidence any dinosaur was venomous – much less a biological supersoaker.

Velociraptor: Too Big, Too Bald, Too Social

The raptors in Jurassic Park are terrifying – but they’re more Utahraptor than Velociraptor. Real Velociraptors were turkey-sized, feathered, and likely solitary. The pack-hunting, human-sized lizard look was more fiction than fact. Feathers weren’t well-known in 1993, so we’ll give Spielberg a soft pass here.

Stegosaurus: Puffing Up The Drama

Stegosaurus is another case of size exaggeration. Nine-foot tail spikes? Not likely. And that adorable baby with puppy-like proportions? Pure anthropomorphic fantasy (sadly). But Loewen does praise the theory that those back plates weren’t for cooling – but for intimidation.

Spinosaurus vs. T-Rex: Who Wins?

On land? T-Rex every time. While Jurassic Park III gave Spinosaurus the upper claw, the reality is that Spino was slimmer, aquatic, and built to fish – not fight apex predators. A T-Rex could’ve crushed its skull in one bite. The scene looks cool, but it’s scientific sacrilege.

Sinoceratops, Carnotaurus & Other Cameos

In Fallen Kingdom, we get rarer species – but with liberties. Sinoceratops is almost unrecognizable, with an oversized horn and implausible moves. Carnotaurus fares better, Loewen even calls it one of the best-rendered dinosaurs in the franchise, thanks to well-preserved fossilized skin. Still, its showdown with Sinoceratops stretches anatomy beyond breaking point.

Final Verdict

Jurassic Park was never a documentary, it was a dramatic portrayal of dinosaurs. While the franchise takes creative liberties – sometimes wild ones – it has also created global interest in paleontology. According to Loewen, this might be the most realistic aspect of all: the way dinosaurs have captured imaginations long after their extinction.