Merchandise or Entertainment Experience?

Starting with the debut title on the Nintendo 64 in 1998, the Mario Party video games have been… interesting, to say the least. The board-game–minigame-compilation-hybrids have consistently succeeded in turning players against each other, but have utilized many different approaches to do so over the years.

But among the titles that still qualify as video games in any meaningful sense (thus excluding the thinly veiled gambling machines found in arcades), perhaps none are stranger than the Mario Party release for the company's obscure e-Reader accessory.

The "Future" Of Trading Cards

The idea for the Nintendo e-Reader emerged from a collaboration between Nintendo, Creatures Inc., HAL Laboratory, and Olympus, with Creatures proposing a way to embed hidden data in their Pokémon trading cards using Olympus' "dot code" technology. The prototype was developed in a few months, and the concept was first publicly shown in 2001 before its commercial release in Japan (December 2001) and later in North America (September 2002).

Functionally, the e-Reader is a cartridge-style add-on for the Nintendo Game Boy Advance that uses an LED scanner to read encoded "e-Cards" with dot code stripes. Players have to slowly swipe these cards through the reader, which decodes the data and transfers it to the GBA. Sometimes, multiple cards needed to be scanned to assemble a full program, since one card strip could only ever contain a maximum of 2.2 kilobytes of data.

The cost of the cards and cumbersome use limited its appeal, making the e-Reader only modestly successful. However, during its lifespan (which lasted until 2004 in the West), it could be used to unlock or enhance content in GBA and GameCube games, with the cards' tiny storage spaces containing data for new levels, items, NES re-releases or – most importantly – minigames.

Separating Board From Game

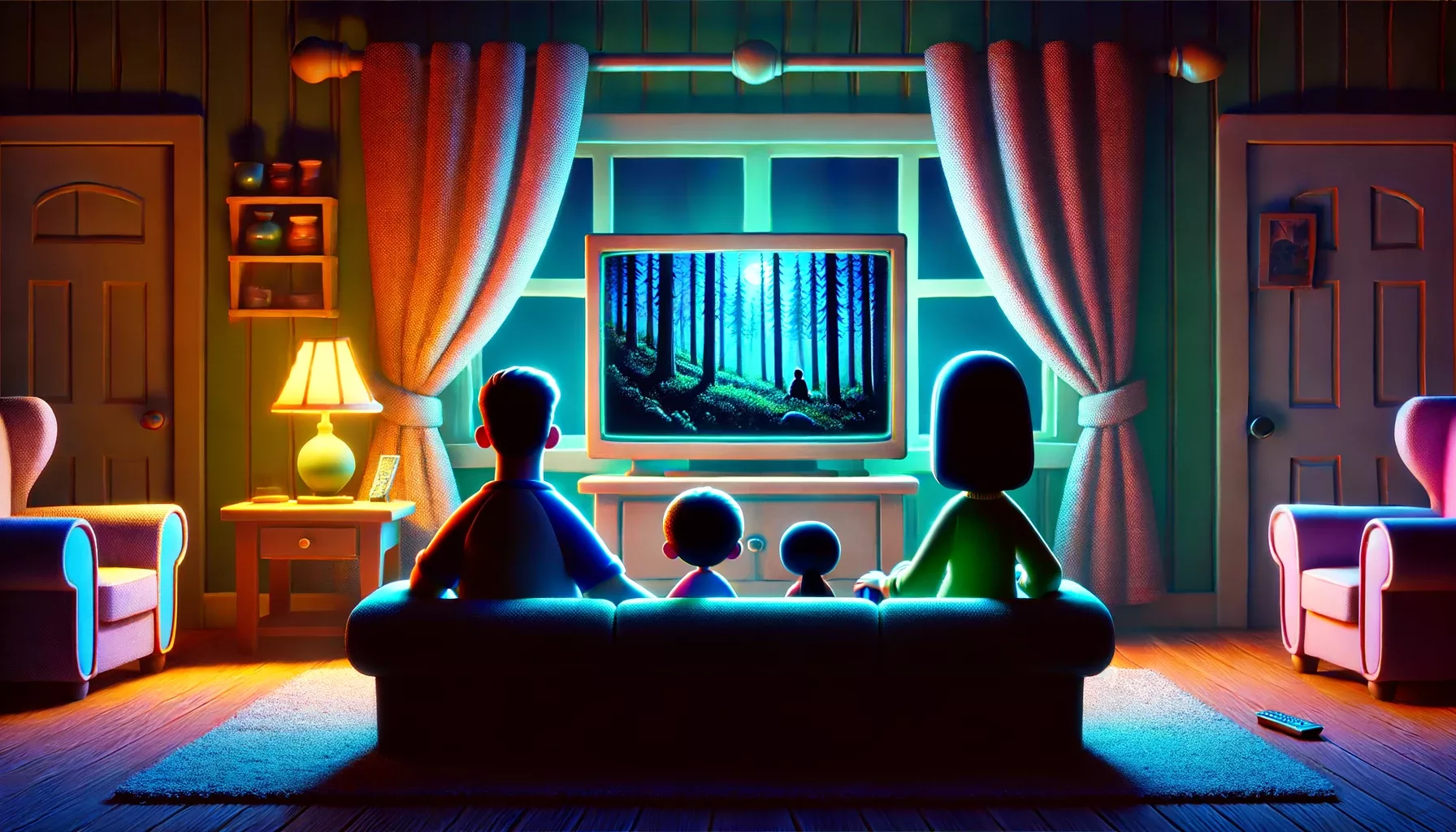

The core gameplay of the Mario Party series has always consisted of two parts: A board game, which sees players rolling dice and moving the corresponding amount of the spaces to reach a star while handling items and event spaces – and the minigames, where players compete in various scenarios for coins with which they can purchase the items and stars on the board.

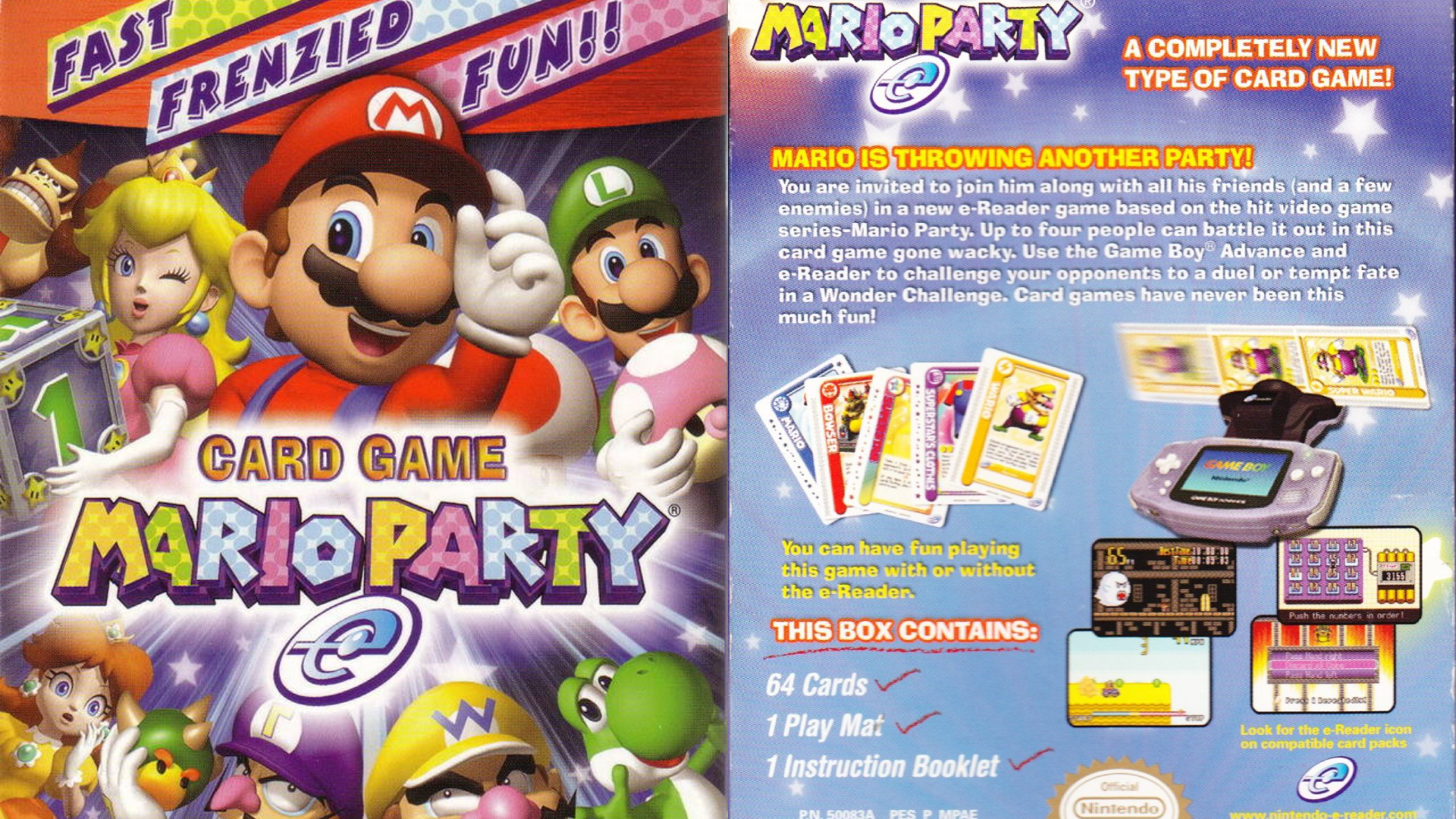

Given this, it's easy to discern Nintendo's intentions when they commissioned studio Indieszero to develop a title which was supposed to help expand the e-Reader ecosystem in North America: A Mario Party where players imitated the board game part via physical cards and a board in real life, while scanning minigame cards to the e-Reader to play them on a Game Boy Advance.

For its artwork and promotional material, this game, which would come to be known as Mario Party-e upon its North America-exclusive launch in 2003, drew heavily from its successful GameCube predecessor Mario Party 4 (2002) and represented a completely new and novel approach to integrating e-Reader functionality into video games.

A Familiar, But Different Party

In regular Mario Party, the aim of the game for each players is to have the most stars when the pre-set turn limit ends. In contrast, Mario Party-e is won by any player who first manages to the collect three Item Cards (Mario's hat, clothes and shoes), place them in the In-Play area and then place the Superstar Card.

Each player begins with a hand of cards drawn from the shared deck. On each turn, players draw a new card and may play one from their hands into the In-Play area or use its effect. Cards are divided into several categories, each serving different functions. The Item Cards are required to win, but they can be protected or stolen through other cards (Blocker, Search, Chaos, etc...), which work similar to the items from the core titles. They sometimes require Coin Cards to use.

In all this, the e-Reader serves as an optional digital enhancement rather than a core requirement. Certain cards can be scanned to activate things like a digital roulette or duel minigames, each determining the outcome of a decision on the board. For example, a minigame enabled by a Duel Card allows the winner to take a card from the loser. If players do not possess an e-Reader, a coin toss is used instead.

Losing At The Final Turn

Critical reception of Mario Party-e was muted: Most Reviewers often treated it more as a novelty or marketing tie-in than a full-fledged game, praising the concept but criticizing its limited depth and reliance on the e-Reader. Though some, like IGN's Craig Harris, argued that potential future booster packs could remedy the allegedly shallow gameplay.

In terms of sales and commercial impact, Mario Party-e never made a major splash, with its North America-only release and niche platform condemning it to a fate as a collector's item. While the e-Reader would be supported longer in Japan, much of its functionality would be removed from Western versions of the games, e.g. events in Pokémon FireRed, LeafGreen and Emerald.

Mario Party-e remained the only title in the series to be developed by Indieszero, with Hudson Soft continuing to develop all games until Mario Part 8 and DS (2007), after which the studio was purchased by Konami, with development duties shifting to studio Nintendo Cube, whose titles have often received mixed reception by fans. It would take until Mario Party 10 (2015) for the series to try a similar toys-to-life approach again, this time in the form of Amiibo.